Drugs and Alcohol, A Crutch for Egocentric Fear

Some may recognize the name Diogenes of Sinope. He was a Greek, cynic philosopher who lived a long time ago – in the third century, B.C. – during the time of Alexander the Great. A surprising number of writers today are about talking about Diogenes. They draw very different conclusions about him depending on the facts they choose to present.

On the one hand, some authors cite him as an ancient icon of rugged individualism. Diogenes is portrayed as self-reliant and independent, the kind of man America really needs in our namby-pamby, politically correct culture. One writer says, “Diogenes is everything I am not. He is quick witted, brash, shameless, mentally and physically tough and above all… he is free.”1 Another assures us that Diogenes epitomizes “living a life in which you make decisions . . . You trust yourself. You’re true to yourself.”2 A Psychology Today article claims Diogenes is the author’s hero.3 They talk about Diogenes like he’s the main character in a John Wayne movie.

According to them, Diogenes lived a self-directed and autonomous life. He prioritized independence and uniqueness. Diogenes shrugged off all social expectations and even laughed at wealth and power. They like to relate an account about the philosopher meeting the great Alexander himself. As the story goes, Diogenes was sunning himself on a city street, and he “raised himself up a little when he saw so many people coming towards him, and fixed his eyes upon Alexander. And when that monarch addressed him with greetings, and asked if he wanted anything, ‘Yes,’ said Diogenes, ‘stand a little out of my sun.’”

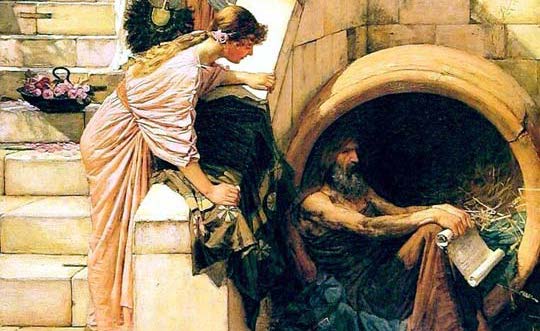

The foregoing sounds great in it’s own way, but every coin has two sides. It’s hard to take these authors seriously when we know all the facts. We’ve included a picture of John Waterhouse’s painting of Diogenes for reference. That’s a good historical rendition of Diogenes on canvas.

In fact, Diogenes’ lived in a big, clay wine jar on a city street. He was homeless, begged for his food, and ate with his hands. Ancient chroniclers describe him as dirty, unkempt, and smelling like filth. Diogenes lived like a dog and called himself one. He explained that “I fawn on those who give me anything, I yelp at those who refuse, and I set my teeth in rascals.” The Greek word for cynic, kynikos, actually derives from the word for dog. Diogenes had abandoned the most basic notions of decency. He not only urinated and spit on those who disagreed with him, but he also made a spectacle out of himself by publicly defecating and masturbating. When asked about his especially mortifying acts of masturbation, Diogenes said, “If only it were as easy to banish hunger by rubbing my belly.”

Diogenes spent his days lying about like a dog refusing to work, and nobody ever dared give him any responsibility. He also held in contempt the ideas of family, property rights, and all social and political organization. Above all, Diogenes was prideful – he considered himself better than everybody else. In his arrogance he ridiculed all those around him. He bragged that he and he alone had found happiness.

We see this second, more complete description of Diogenes as much different, and altogether more telling. We don’t see someone whose self-reliance proved to be fulfilling. The real Diogenes looks more like the proverbial boy who, when the game isn’t going exactly his way, decides to take his ball and go home. Unable to cope with his defeats, his fear of failure led him to quit. Sadly, the game that Diogenes walked out on was his own life.

History doesn’t give us the particulars, but it’s easy to see how this happened. We’ll grant that Diogenes had some intelligence and talent, but his ego was working on overdrive. Being a legend in his own mind, Diogenes merited fame, fortune and power. What he got was less. Before he even moved into his clay jar, Diogenes couldn’t keep up with the Jones – either socially or economically. The results of his life’s efforts must have seemed like crushing disappointments. He was terrified to admit that he was like everybody else, and he probably lived in constant anxiety that he was ordinary, wasn’t good enough, or would be found out. Diogenes’ ego told him he was better than that. Much better. Why didn’t they grant him the accolades and perks he deserved? It must have seemed like an abomination how they repaid his genius. He was living like a commoner. Couldn’t they see he was different? Didn’t they know he was special?

The fear of never getting his reward, of never amounting to anything, must have been immense. Diogenes eventually reached a turning point in his life, a mid-life crisis where he just snapped. He boomeranged. He was better than those plebeians, he reasoned. They could have their beautiful homes, their loving wives and children, and their important jobs and social standing. He didn’t need all that – he didn’t need anything. He’d rather live like a dog than run in their rat race. He’d show them who’s best. He and he alone would be best – at having nothing! He would rub their noses in it by flaunting a deliriously happy appearance, for good measure.

The historical record does not expressly show that Diogenes was an alcoholic. For us at CORE who are recovered alcoholics and addicts, all we have to do is imagine the scent of distilled spirits on Diogenes’ breath, and he really starts to remind us of somebody. Somebody whose existence we knew all too well. Before we recovered, we were afraid to face our own lives too, and we also quit the game. Thus, rather than being an idol for self-reliance and independence, we think that Diogenes preferably illustrates a puffed up ego overreacting to crippling fear. He would make a better poster child for the alcoholic or addict trapped in the cycle of addiction.

The Big Book describes just such a person:

We asked ourselves why we had them [i.e., fears]. Wasn’t it because self-reliance failed us? Self-reliance was good as far as it went, but it didn’t go far enough. Some of us once had great self-confidence, but it didn’t fully solve the fear problem, or any other. When it made us cocky, it was worse.

Big Book, at 68. In our active addictions, and probably before, we subsisted in the fear of not getting what we deserve out of life. Our egos were out of control. We made our demands upon ourselves and those around us so onerous that we unwittingly trapped ourselves in an untenable situation. Thus, if we didn’t get exactly what we wanted, or if somebody failed to reciprocate our feelings exactly as we demanded, then we assumed the worst. We considered ourselves losers or thought that we were being rejected. It was an unwinnable game that brought only frustration. The ego’s fear of failure jumped up and down in protest, shouting that we didn’t do anything wrong or that they didn’t deserve us. It assured us that we were justified indulging in fear’s ultimate expression – quitting. We quit a hundred times, thousands of times, into the ease and comfort afforded by the first drink or drug. Like Diogenes, we took our ball and went home.

We were driven, as the Big Book says, “by a hundred forms of fear, self-delusion, self-seeking, and self-pity.” Id., at 62. It’s no accident that fear shows up in each and every 4th Step inventory example offered by the Big Book:

This short word somehow touches about every aspect of our lives. It was an evil and corroding thread; the fabric of our existence was shot through with it.

Id., at 67. Our fear typically was the result of an overinflated ego seemingly under constant attack. We were “self-centered–ego-centric.” Id., at 61.

If we were to live, to recover, this conceited absorption in ourselves, the insanely self-centered attitude, had to be dealt with. The main problem of the alcoholic or addict “centers in his mind, rather than his body.” Id., at 22. This is why humility is an overarching theme in the Big Book. The “leveling of our pride” is required for successful consummation of the 12 Step process. Id., at 25. Each step in some way presents an opportunity to deflate a pathologically, out-of-control and thoroughly self-centered ego.4 Moreover, even while our troubles were basically of our own making, we were powerless to help ourselves. Divine help was needed to restore us to sanity:

God makes that possible. And there often seems no way of entirely getting rid of self without His aid. . . .Neither could we reduce our self-centeredness much by wishing or trying on our own power. We had to have God’s help.

Id., at 62. We went to the One who has all power – a power greater than ourselves. We found Him in the surrender and house-cleaning program of the 12 Steps.

Now that we have recovered, one might ask, how do we respond to everyday challenges of life? Like normal people, we think. Every day we affirm in prayer our intent to undertake God’s will, without self-centeredness or pride. Our egos are no longer thin-skinned, easily wounded, and demanding of quick and utter victory in every undertaking. We live in gratitude with helpful, patient, and forgiving spirits. We pause when agitated or doubtful and ask for the right thought or action. Id., at 87. Fears do not paralyze us, however. If they arise, we ask God to remove them and direct our attention to what He would have us be. Id., at 68.

Something wonderful happened when we began to live without fear:

As we felt new power flow in, as we enjoyed peace of mind, as we discovered we could face life successfully, as we became conscious of His presence, we began to lose our fear of today, tomorrow or the hereafter. We were reborn.

Id., at 63. We became people of courage. It is our privilege and honor each day to let God demonstrate through us what he can do.

1. https://medium.com/@philosotramp/why-diogenes-of-sinope-28885ec6cc86

2. https://www.artofmanliness.com/articles/finding-true-north-guide-self-reliance/

3. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/201203/my-hero-diogenes-the-cynic

4. We will present one for each step here. A full account would take another essay:

Step One: “Until he so humbles himself, his sobriety–if any–will be precarious.” 12&12, at 21.

Step Two: “There had been a humble willingness to have Him with me.” Big Book, at 12.

Step Three: “This was only a beginning, though if honestly and humbly made, an effect, sometimes a very great one, was felt at once.” Id., at 63.

Step Four: “to the extent that we do as we think He would have us, and humbly rely on Him, does He enable us to match calamity with serenity.” Id., at 68.

Step Five: “But they had not learned enough of humility, fearlessness and honesty, in the sense we find it necessary, until they told someone else all their life story.” Id., at 73.

Step Six: “As they are humbled by the terrific beating administered by alcohol, the grace of God can enter them and expel their obsession.” 12&12, at 64.

Step Seven: “Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.” Big Book, at 59.

Step Eight: “It had been embarrassing enough when in confidence we had admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being. But the prospect of actually visiting or even writing the people concerned now overwhelmed us . . .” 12&12, at 79.

Step Nine: “We should be sensible, tactful, considerate and humble . . .” Big Book, at 83.

Step Ten: “When prideful, angry, jealous, anxious, or fearful, we acted accordingly, and that was that.” 12&12, at 94.

Step Eleven: “We constantly remind ourselves we are no longer running the show, humbly saying to ourselves many times each day ‘Thy will be done.'” Big Book, at 87-88.

Step Twelve: “Tell him exactly what happened to you.” Id., at 93.