Scott Bourbon: Nothing Left to Chance

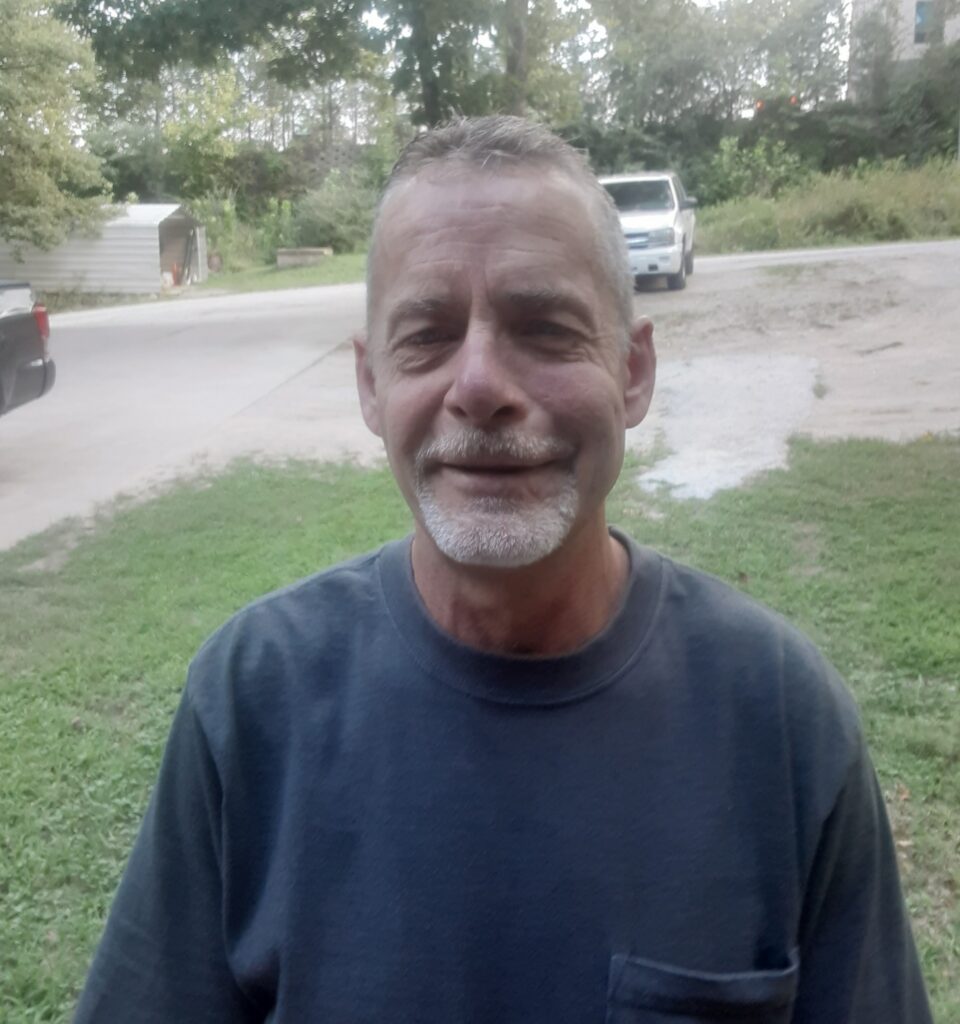

This month we spoke with Scott Bourbon! He’s currently a manager at our Bird House in Branson. Right out of the gate, he radiated the practical wisdom that comes with five years of recovery.

As an example, we talked about the Big Book, which teaches that addicts suffer from an illness which only a “spiritual experience” will conquer. When it was remarked that newcomers sometimes have difficulty understanding this phrase, Scott shifted into house manager mode. He explained how the essence of a spiritual experience can be found in simple, heartfelt gratitude:

Driving to work in the morning, when the sun is coming up, I look around and thank God for that moment. Thank you for this day, right now. I know what is waiting for me if I ever go back. And people say that it’s not going to happen for you. It happens. I don’t know if I ever had some kind of lightening thing light me up, but I do know this, I’m content, and happy. My life is together, I enjoy it, and I don’t need that junk in my body. As far as I’m concerned, that’s THAT moment they’re talking about. The spiritual experience. I have them all the time if that’s the case, because every day I am grateful.

We can’t help but smile at his observations. Scott is a consummate teacher. He uses his own life experience to illustrate his points, and he’s always ready to share.

When it comes to working the 12 Step program, Scott says “I don’t leave anything to chance.” To him, chance means chaos, the proverbial thief that kills, steals, and destroys. To illustrate, he rattles off seven names in succession. We aren’t familiar with these people, but Scott knows them. They are his friends and loved ones, companions with whom he ran for decades in his addiction. One by one, each died in the months following his arrival at CORE. Some overdosed, another was in a car accident, and others suffered various mishaps, but all of the calamities were occasioned by drug use. Reflecting on this, he says, “If I hadn’t come CORE, I’d probably be dead too, or locked up for a really long time. I’d have made some kind of mistake, too.”

We can’t detail his life as an addict here, but we can paint the picture. He regularly kept alcohol and pills at his night stand because he couldn’t get out of bed without them. He also remembers “going into seizures if I didn’t have pain pills, or dope, or alcohol.” On countless times, he woke up in the hospital connected to tubes and machines. He’s been to more rehabs than can be counted on both hands and feet. He also was a regular at the county lock up. “It got to the point where I’d just shine that off,” he recalls, “I didn’t really care anymore. I figured that was my life.”

The foregoing will sound familiar to anyone who’s struggled with substance abuse. On top of everything, Scott’s family, children, and career became casualties of his addiction, too. They seemed long gone, and Scott had no hope of ever hearing from his children again.

He heard about CORE for the first time when somebody mentioned it at a Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meeting:

I’d walked over to this place called the 2116 Club. They held NA meetings that I went to off and on over the years. I’d just left the hospital . . . almost went to 711 to get something to drink, but instead went to that meeting. There was a girl who’d been in CORE. I’d never met her in my life. But, she overheard me talking to someone and said, hey, do you want a way out? Ever hear about CORE? I had no idea what it was, but she gave me the phone number. I called and showed up four days later. God stepped into my life that day.

Scott “never looked back” after discovering what CORE is all about. He was ready to put 38 years of addiction in the rearview mirror.

He insists that CORE is different from other programs, saying “you can’t find a program comparable to CORE in this country” and “They do a good job of explaining the 12 Steps. By just doing the things that they suggest to you, I guarantee this program will save your life.”

Scott also shared with us three things he believes were important to his recovery. He now shares these items as advice for the guys in his house about working their own programs.

The first is to listen. There’s a lot of recovery at CORE. As an example, our downstairs administrative staff who’ve been through our program – just four people – have over 60 years of recovery between them. And CORE’s a much, much bigger place than that. Everybody within the organization wants to help. Scott elaborates, “It finally hit home that all I had to do was listen. All I had to do was listen, and try something. And it absolutely has been wonderful. Everything I expected, happened, just by listening.”

Second, aspire to daily growth. Whether it’s one thing or many doesn’t matter; just make progress. Using himself as an example, again, Scott says, “You can’t do this half-hearted. Everyday I wake up and think, I’m going to do something a little bit better today than I did yesterday. I still have defects of character, but no doubt I’m not the same person I was four or five years ago. And it just keeps getting better.”

Finally, stay focused on the 12 Step program above other concerns, and be patient for the recovery blessings to happen. Upon finding sobriety, Scott initially felt pressure to leave CORE, to establish himself, and to show everybody he was doing well. After prayer and consideration, he decided to focus on recovery, and he stayed (“Something inside me – I just thought, I have to do this and make recovery my priority.”)

We’re happy to report that his patience and diligence were rewarded. Scott is reunited with his sons. Now, they see each other (grandchildren included!) when they are able, and they also talk regularly on the phone. In fact, the night before our interview, he’d spent two hours with them on the phone. He adds, “And every day, I text my family in the morning, just to tell them good morning, I hope you have a great day. I always end it with, love you, because – those are really important things (voice wavering).”

All in all, we’d say Scott’s advice is well taken at the Bird House. Several guys recently commenced, and more are due to complete our one-year program this autumn. This makes over ten (he’s counting in his head) who will commence out of the Bird House in roughly a year.

One of Scott’s sons has suggested that he come live near them, but Scott believes that there’s still more to accomplish here in Branson. We understand his feelings. He has a great career here and cares about the people he works with. His work at CORE is greatly appreciated, too. Scott also mentioned that his weeks just don’t seem right unless he attends our Friday night church services. Whatever he decides, we support him 100%. We’re happy knowing that, wherever he goes, Scott will let his light shine brightly, and he’ll give God all the glory.